When former Gawker writer Emily Gould scored the cover story of the Times Magazine in May 2008, people got pissy. Then-26-year-old Gould’s piece ran to just under 8000 words, and was a memoir of sorts, detailing her exploits as a personal and professional blogger. The piece received over a thousand online comments, most of them outrageously negative. One of them, by ‘bill of cambridge’, read in part, “it all seems so remarkably self-indulgent and yet so completely trivial, no offense. really, the details of your life are no more interesting than those of anyone else’s. they are of interest only to you and those who care about you.”

Wanting to tell your story is a tricky business. You leave yourself open to charges of selfishness and egotism: after all, what makes you think we’d want to read about you? One way to counter that might to say, “Well, actually, I’m not writing about myself. I’m writing as a [Jew/orphan/prostitute/blogger/insert-exotic-identity-group-here].” But then, of course, you find yourself screwed again, because what right do you have to act as the spokesperson for whatever social group you happen to be a part of? What right did Gould have, for example, to write on behalf of bloggers everywhere?

Clearly, writing a great memoir is a hard ask. You need to make sure your work can’t and won’t be construed as an exercise in narcissism, and you need to situate yourself as speaking as a member of some social group, without placing yourself on a pedestal as speaking for that group. God, you end up thinking, this is too tricky. Might as well stop writing now.

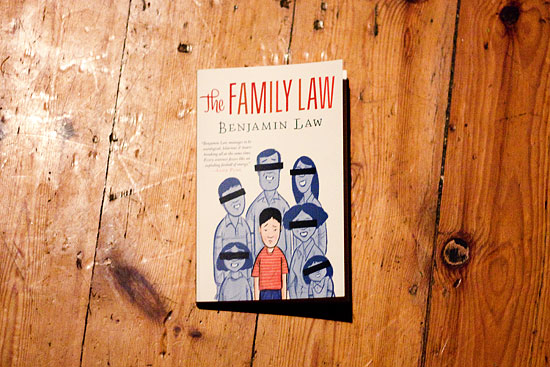

Benjamin Law is second-generation Asian-Australian, funny, and gay. His collection of personal essays, recently published as The Family Law, is a precarious balancing act. Law is self-deprecating (as a kid, little Benjamin pees the bed after watching Stephen King’s It; later, he anxiously wonders whether all teenagers enjoy Mariah Carey’s Music Box as much as he does), saving him from charges of arrogance. And he manages to situate himself as a young, gay, second-generation Asian-Australian, without coming off as the ‘official spokesperson’ for every young, gay, second-generation Asian-Australian out there.

In the twenty-plus pieces that comprise The Family Law, Law never drags us along under the promise that his life experiences contain profound truths. Law writes to entertain. My first LOL-out-loud moment came on page 5, imagining Minnie Mouse running out of the Disneyland castle, hands on cheeks, screaming, “I was raaaaped!” I tried to count the references to dicks and vah-jarn-ahs, but gave up after page 10.

Still, like all great humorists, Law’s talent is that his seemingly throwaway quips more often than not cloak penetrating truths. It would take me way too many words to explain how Law manages to turn a story about his mother learning the word ‘cunt’ into a sincere, heartfelt examination of shifting cultural identity. But do you really want to read a ‘sincere, heartfelt examination of shifting cultural identity’, or do you want to read a bunch of fifth-graderish jokes about veejays and peens? That’s what makes Benjamin a bit of a genius: he bundles one with the other. And not once does it seem trivial. Not even the monstrously oversized, winking paper labia.